Book Review: “The Director” — To Collaborate or Not to Collaborate, That Is the Question

By Steve Provizer

This wake-up call — what will artists be asked to do to please the powers-that-be? — is also a good read.

The Director by Daniel Kehlmann. Translated from the German by Ross Benjamin. S&S/Summit Books, 352 pages, $28.99

Artists of all stripes find themselves trying to come to terms with their place in a world edging toward fascism. There’s been a lot of buzz around the political drama at the center of The Director, and that, as a writer and musician, drew me to the novel. For a change, the buzz was right. The interlocking themes German author Daniel Kehlmann weaves together in this accomplished work of fiction provide a number of ways to contemplate people’s relationship to overweening power — whether they are artists or not.

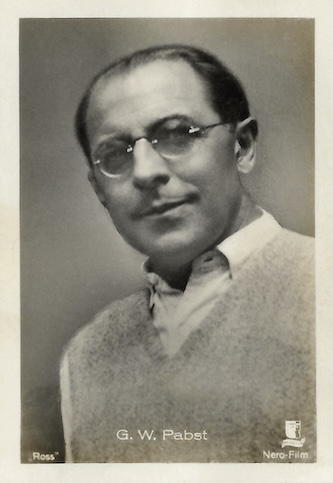

The backbone of the novel is the relationship between the Nazis and film director G.W. Pabst, perhaps best known for Pandora’s Box (1929) and Threepenny Opera (1931). Chief propagandist for the Nazi Party Joseph Goebbels (known in the book at the Minister) made the filmmaker’s situation crystal clear: Do what we want you to, or you and yours will be sent to a camp. This transparently authoritarian setup is a double-edged sword when applied to what is going on in America today. The edict provides clarity and intensity, but, because Nazism has become the paradigm of evil, it’s challenging to draw moral analogies to the more mundane, or “banal,” examples of strong-arming we are currently experiencing.

Admittedly, to people facing arbitrary deportation, this fine distinction is moot. But for most of us, dealing with the Trump administration has not become life-threatening, so the parameters of what actions should be taken are not obvious. The crux of creative compromise remains self-censorship. These decisions can be rooted in protecting money and status: will I or my organization be punished (defunded by the government, banks, or philanthropies) if dissenting social media posts are discovered? Or it can shape emotional relationships. If some suspect that a despicable character in my novel, play, or film resembles my brother, do I have the nerve to deal with the consequences at the family Thanksgiving table?

As I write, artists are trying to come to terms with how they will shape the broader culture. Will they address the fact that democracy is at risk, potentially alienating people who want the arts to be entertaining, to take their minds off what is happening around them? Should artists fight self-censorship by becoming more barbed and satirical? Should one occupy oneself with more “serious” subjects, particularly work infused with more specifically political content? Are creatives called to be dissenters?

One way to try to understand how The Director relates to these questions will depend on the degree to which the reader identifies with Pabst.

Pabst, seemingly, was unfit for anything other than making films. Except for his unrequited love for actress Louise Brooks (star of Pandora’s Box), he was at his most comfortable relating to humans on a film set. For him, life and art were interwoven. He saw film scenarios everywhere he looked, a process that Kehlmann deftly dramatizes. Here the cinephile is trying to escape Prague for Vienna. He sees it as a film that he is editing on the fly: “Pabst had become so attuned to film editing that it seemed to him he would continue out here as if everything he saw were up for manipulation.” Pabst contemplates how he would smoothly cut together camera shots, including soldiers, roads, and escape paths.

We are taken out of Pabst’s mind and given alarming glimpses of the matrix of violence and power that demands artistic compromise. Authority’s threats are a miasma that envelops each scene. Kehlmann carefully calibrates the shifts in dominance and submission between the protagonists and the Nazis and among the fascists themselves. The scenario is self-consciously Kafkaesque (Kehlmann recently co-wrote a six-part biopic of the author). The Director zeros in on the terrifyingly arbitrary, paranoid nature of unquestioned control: how it is won and how it can be taken in an instant.

A cigarette card featuring G.W. Pabst.

This exploration of the mechanics of power rings frighteningly true, except for the way Kehlmann deals with Pabst’s wife Trude. She has been reduced to pure victim, a self-mutilating shell of a self, demolished by Pabst’s collaboration with the regime as well as her son’s easy acceptance of Nazism. Near the end of the book, she is suddenly put in charge of filming her own screenplay. Her husband is allegedly the director, but she has been given the authority. Kehlmann doesn’t effectively dramatize how this turnaround came about.

In real life, Pabst had no son, but Kehlmann gives him one in the book. Jakob’s arc demonstrates how violence was inculcated and normalized in the lives of German youth. He also serves as a metaphor for the fragility of the artistic sensibility. Jakob has a natural aptitude for drawing and he continues to sketch even as he goes through training as a Hitler Youth and then becomes part of the German army. He is in the tank corps and his tank is hit — his fingers badly maimed. At first, it comes off as a bit too neatly allegorical, but then Kehlmann adds welcome complication. After Pabst has died, Jakob travels to America to give Louise Brooks a present from his father. She tells him that his father told her that Jakob was a talented artist and asks how it’s going. He responds that, because of his injury, he stopped drawing. Brooks rejects that excuse: “The soul is quite sensitive.… Life bends everyone, but it breaks some brutally and early. You and me, for example.” Brute force need not (must not) bury art.

Those embroiled in the immigration fiasco may read The Director and feel America has already arrived at that level of brutal governance. My sense is that there is significant popular pushback against Trump, his oligarchic buddies, and masked ICE thugs. Some in the artistic community who speak out are being punished for doing so, but at the moment, The Director‘s vision of political shutdown is more of a cautionary tale than a dead-on reflection. That said, the novel provides guideposts that will make artists (and others) more sensitive to the gradual rise of fascism.

A coda: In this review I’ve focused on the novel’s social relevance, but there are plenty of subplots, dramatic episodes, black humor, and cameo appearances by Leni Reifenstahl, Greta Garbo, and a thinly veiled P.G. Wodehouse. The Director carves out a compellingly viable space between fact and fiction. So this wake-up call — what will artists be asked to do to please the powers-that-be? — is also a good read.

Steve Provizer writes on a range of subjects, most often the arts. He is a musician and blogs about jazz here.

Source link